An Explosion of Life: Julia Lambright’s Flowers in Simple Things

From a biological perspective, flowers are reproductive organs. But metaphorically, flowers symbolize ideas, including beauty, grace, femininity, wealth, luxury, and the essence of life. A popular subject in art for millennia, flowers have been depicted in a wide range of styles and mediums. In ancient Roman frescos depicted lush gardens suggesting springtime all year long, bringing the warmth of the sun to every room.

Still-life paintings featuring flowers were popular in the Baroque era from the sixteenth- and seventeenth centuries when artists used fruits, flowers, and luxury items to showcase their technical skills and attention to detail. Often set against a dark background to create a sense of depth and drama, Baroque painters depicted tables laden with glass cups and vases, silver and gold plates and bowls filled with all sorts of food – breads, cheese, meats, ripe fruits and colorful vegetables, and finished with bouquets. Known for their technical skill and attention to detail, painters like Willem Kalf, Rachel Ruysch and Clara Peeters produced almost three-dimensional detailed images with bright rich colors and details possible due to the use of oil paint. Perfected in the fifteenth-century, oil paint was made by mixing powdered pigments with oil and drying solvents and applied in many layers results in images with rich colors, luminous and bright yet precise enough to give exact details. These paintings feature wild flowers each with their own meanings, such as carnations for pure love and fidelity; cyclamen for devotion, sincere heart, and empathy; foxglove for riddles, and secrets; iris for faith, hope, courage, wisdom and admiration; larkspur for a beautiful spirit, swiftness and generally of positivity and strong bonds of love; and lilies for a beautiful spirit, swiftness, and the strong bonds of love. While the foods and flowers in Baroque still lifes are fresh and lush, the artist’s invariably include a reminder of the fleetingness of life. With a few petals dropped on the table, flies buzzing around the food, and fruit on the verge of rotting, the artists offer a memento mori, a reminder that life, while beautiful and rich, is also finite and fleeting, that living is also the process of dying.

In the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movement, artists began to use flowers as a way to explore color and light. Artists such as Claude Monet, August Renoir, Mary Cassatt, Paul Gaugin, and Vincent van Gogh used bright, vibrant colors and loose brushstrokes to capture the beauty of flowers in bloom. Van Gogh’s iconic sunflowers relate to his family history as the son of a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, as the sun moves across the sky, the sunflower turns to follow, almost like a disciple. Native to Peru, sunflowers refer to Paul Gaugin, whose mother was Peruvian. The sunflowers and irises in van Gogh’s paintings capture the wild lushness of life

Flowers, especially wild flowers, are recurring themes in the work of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Inspired by Mexican Indigenous art and culture, his sunflowers especially capture the beauty and vitality of Mexican culture. Rivera's Flower Festival: Feast of Santa Anita depicts women carrying flowers as offerings for the Feast of Santa Anita. His Calla Lily Vendor contrasts the pristine beauty of the flowers with the back-breaking efforts of the seller, his stoic expression suggesting the resilience of the Mexican people in the face of adversity.

In the 1920s, Georgia O’Keeffe magnified and abstracted the flowers, making them appear larger-than-life and focusing on their intricate shapes and colors. She began painting close-up details of flowers, like the stamin of a calla lily, finding the abstract elements in the organic forms. Paintings like Jimson Weed, a large white flower on a black background, and Black Iris, a close-up view of the flower's delicate petals and dramatic, contrasting tones, offer a striking simplicity and focus on its form. O’Keeffe stated: “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it's your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else. Most people in the city rush around so, they have no time to look at a flower. I want them to see it whether they want to or not.” Inspired by the beauty of nature, her flower paintings offer a meditation on the fleeting nature of life and the beauty of the natural world.

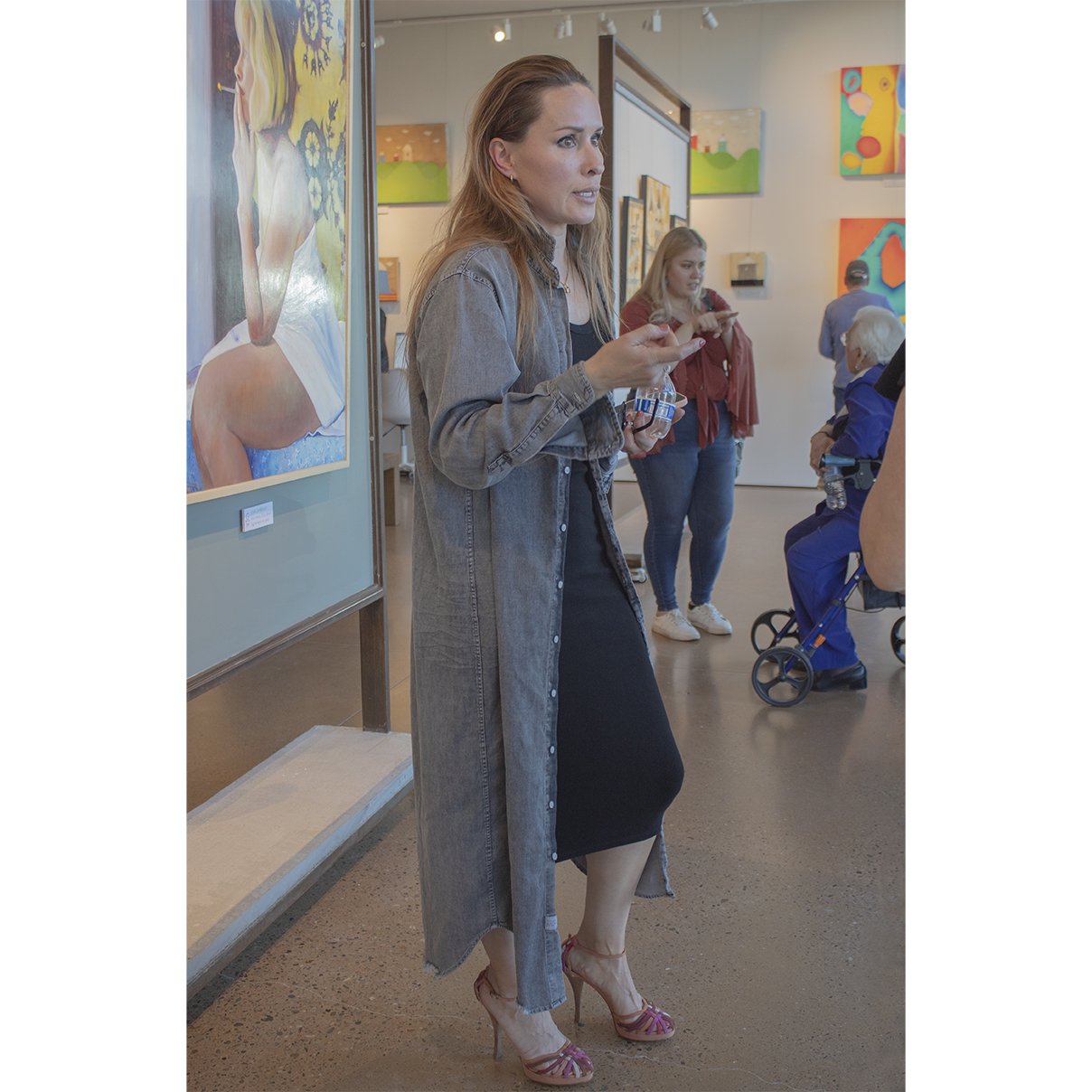

Flowers play a pivotal role in Julia Lambright’s new series Simple Things, with pieces that embrace the beauty in the small things in the world. These works serves as an antidote to the global traumas of the past few years – from pandemic to cultural upheaval to political crises. Lambright’s flowers, unlike Baroque still lives, are not memento mori, or remembrances of death. Rather, they embrace the energy and chaos of life, full of joy and passion, articulating the artist’s ability to move beyond her own afflictions and to appreciate the life around her. For example, Fall Prelude, which depicts a bouquet of flowers in egg tempera and oil paint on panel, is bright, textural, and fresh, a cosmic explosion of light and color spilling out on the table like a nebula birthing a star. In paintings like Pink Duet and Spring Cut, Lambright shares fully bloomed flowers at their open peak; with the darker center, the petals open to invite pollinators, to continue life.

In Simple Things, Lambright shares her enthusiasm for beauty and for life. Taken from the world around her, these paintings and pastel drawings provide a constant springtime energy.