Darby Raymond-Overstreet

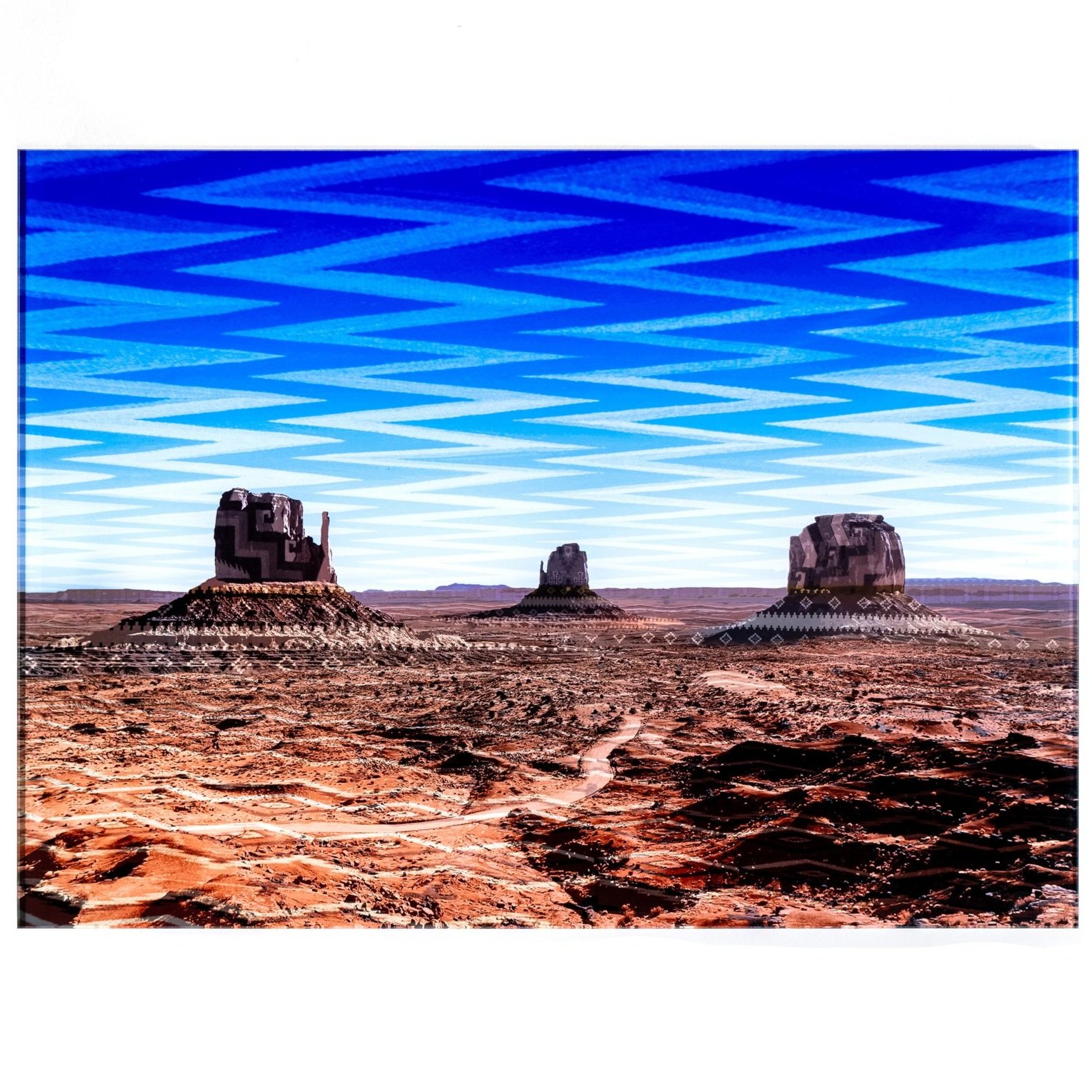

Darby Raymond-Overstreet is an award winning digital artist and printmaker. Born in Tuba City Arizona, and raised in Flagstaff Arizona, she is a proud member of the Navajo Nation. She received her B.A.s in Psychology and Studio Art and graduated with Honors from Dartmouth College in 2016. She currently resides in Chimayó, NM and through her work she studies, works with and creates Navajo/Diné pattern designs that materialize through portraits, landscapes, and abstract forms. Her work is heavily inspired by and derived from Traditional Diné/Navajo textiles, with particular interest in pieces woven in the late 1800's-1950's.

As a printmaker, I explore what it means to be a part of something and how identity is formed. Coming from a mixed racial background, my identity has often been explained and understood by others in terms of parts, but I don’t experience my identity in parts. I experience the wholeness of myself through the relationships that I have to my kin. So to examine this feeling of wholeness I create arrangements of pattern designs, cut them apart, and splice them together in compositions that through the process become something different yet whole again. Each individual piece takes on its own particular meaning, usually, relating to place, emotion, and memory.

As a Diné artist, working with patterns is the most illuminating way for me to explore and expand my understanding of the world. Much of my work is about identity. I’m interested in how cultural practices of art influence and inform collective identity, and how our relationships to our ancestries, our contemporaries, and our descendants culminate to define personal identities and perspectives. As a digital artist, I create cultural portraits that describe modern day Diné in the visual language of our heritage. I merge the artistry of traditional woven textiles into the format and medium of digital art, and suspend the works in traditional looms. These works emulate the duality of Indigenous traditionalism and the adaptation to western society that shapes much of today’s Diné experience. I use woven patterns in my portraits as a way of both reclaiming and celebrating our visual cultural aesthetic. Prompted by rampant cultural appropriation by corporate industries, I find it an apt response to show who these designs come from and for whom they were made. The works also serve as an homage to weavers and the practice of weaving itself.